Screen printing is a favourite for custom clothing and art prints, because the printing process can be fast, repeatable, and easy to automate. A screen print is essentially a very advanced stencil that uses fabric mesh to hold ink-resistant masks in place. Creating a printing screen usually involves applying a special photosensitive emulsion to fabric mesh stretched over a frame, and then developing the screen with a design in a similar way to making a photographic paper print. It’s not a difficult process, but it does require special equipment. You can also make simple screens by applying pre-cut vinyl directly to the mesh, but the vinyl can’t be cut into very intricate patterns. In this article, you’ll see how you can use your laser cutter to short-cut the process, and get printing with the minimum of fuss.

If you’re going to get into screen printing, then you’re going to need a screen. Making a screen is easy and, if you’ve ever stretched a canvas, you’ll be familiar with the technique. Begin by cutting some wood to make a square about the size of an A4+ sheet of paper (250 mm × 337 mm). You don’t have to make a fantastic job of the jointing, as long as the pieces hold together and are flat, with the sides at right angles. Staples, glue, and brad nails should be fine for holding the frame together.

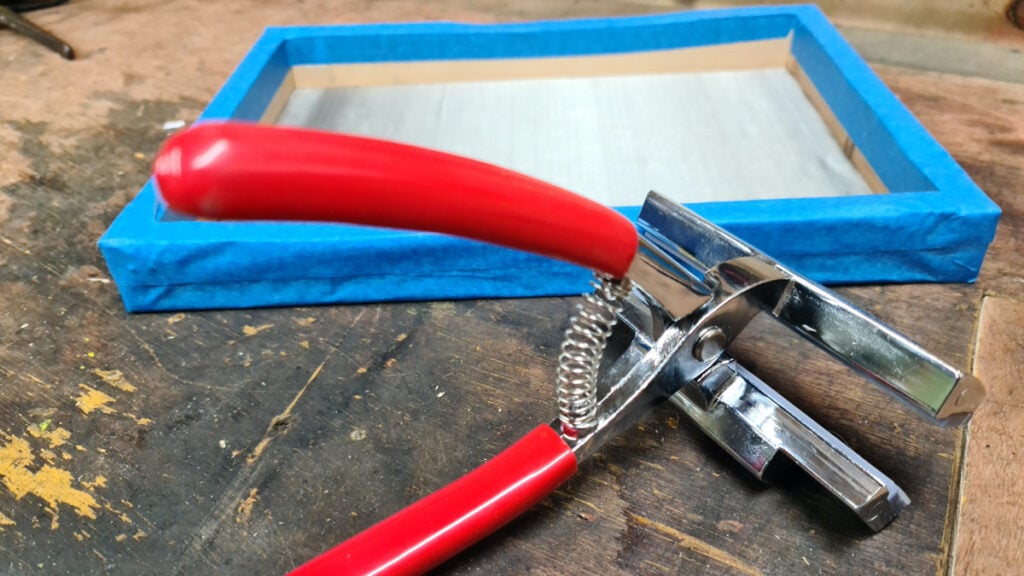

On a normal screen printing frame, the mesh will be made of nylon, silk, or some other fabric. To work with the laser, you’ll need something more resilient than textiles. Take a piece of stainless steel mesh large enough to stretch around the frame, and staple it to one side, pulling the mesh tight as you go. The tension of the mesh on the frame is important to get good prints, so keep the mesh as tight as you can. Work your way around the frame, stapling the mesh in place and drawing the tension. Once you’ve fixed the mesh in place, go around with some extra staples to make doubly sure. You can use some masking tape to tidy up the edges of the frame and protect your fingers from any sharp strands of mesh.

You don’t need photosensitive emulsion for the lasering process: you’ll be using acrylic spray paint. Apply a few thick coats of acrylic spray to both sides of the mesh. The paint needs to totally seal the mesh. You can check this by holding the screen up to a bright light and making sure you don’t see any pinpricks of light shining through the acrylic. Two or three coats of paint should be enough to seal the screen completely.

Once the mesh has dried for a couple of hours, you can load the frame into the laser cutter and etch your design into it. It’s best to position the frame with the mesh side closest to the laser, leaving a void below. Detail is critical, so don’t forget to adjust the height of the frame to match the focal point of the laser. It might be tempting to etch the design in a single pass, but applying too much concentrated power on small details can generate enough heat to damage the steel mesh. Make four or five laser passes with a lower power (10–15 percent of full power at 200 mm/s, depending on the laser) to get the best result. It should be obvious when the mesh is completely etched, as you’ll be able to see through the etched sections. Hold the screen up to a bright light to double-check you’ve got a good, even etch. Give the screen a quick wipe with some water and a soft sponge to get rid of any residues from the etching process, and let it dry.

You’re ready to screen-print, so grab some ink, a squeegee, and something to print on. Proper screen printing jigs hold the frame slightly above the surface that you want to print on. That’s one of the reasons that tensioning your frame is important. You need to be able to push the screen down onto the surface and have it spring back up again behind the squeegee as it moves along. You don’t have a fancy frame, but you do have the next best thing, which is a few 2 p coins. You can stack or tape coins to the corners of your frame to keep it slightly raised from the print surface. It might look a bit odd, but it will work.

Take your frame and place it on the object you want to print. Put some ink at one end of your screen, and use your squeegee to pull the ink across the frame without pushing down. This is called flooding or a flood pass, and the idea is to spread the ink across the screen, to improve print quality and to prevent water-based inks from drying in the mesh of the screen and blocking it between prints.

Now, draw the squeegee across the screen again, this time pushing down gently onto the print surface as you pull the squeegee along. If you feel more comfortable, you can push the squeegee rather than pull it. Remove the frame, let the design dry, and repeat as necessary. You’ll probably need to make a few practice runs before you figure out all of the variables. The thickness of the ink, the amount of pressure you apply, distance between the frame and the print surface, the fineness of the screen mesh, the material you’re printing to, and even the temperature of the room make a difference to the final result.

If you’re really struggling with the squeegee and find that you can’t get a good image, then chances are that the problem is with your ink or with the screen itself. If the screen is blocked by dried ink, or hasn’t been fully etched, you won’t be able to get a good result. If the viscosity of the ink is wrong, you’ll have trouble controlling the flow of ink onto the print surface. If you’ve been fiddling around for a long time and your frustration levels are rising, try using the screen as a simple stencil, and test it by dabbing ordinary acrylic paint through the screen with a sponge or stiff brush. If you still don’t get an image from that, then try using a frame with a coarser mesh, or thinning the ink.