We love the arcades of yester-year, the vibrant colours and sounds that fill the air, designed to entice us to put another 10p into the slot (OK, 50p these days). These arcades are dwindling, largely due to home consoles being so powerful and fostering large communities of gamers. But for those of us who enjoy the arcades, we dream of owning a cabinet, or even building our own. Thanks to the Raspberry Pi and RetroPie, we can make that dream real; all we need to do is make a cabinet.

But what if you haven’t got the space? Well, a tabletop cabinet is possible, but we can go even smaller and, using the ‘Mini Arcade Cabinet’, we have a ‘donor cabinet’ that we can use to create our own miniature cabinet. So dear reader, let’s take a look at a £20 cabinet that may just help us create our own miniature nostalgia trip!

The stock machine

Our new toy cost is £19.14 from hsmag.cc/LTgVEL. Powering up the machine and taking it for a spin, there are four categories of games: ‘Sports’, ‘Shooting’, ‘Puzzle’, and ‘Arcade’. Inside of these categories we find a mixture of unlicensed games from the early 1980s, Flash games, and some very dubious clones of popular games. Sure, they are fun and we spent a good hour playing as part of the tear-down, but we can have more fun building our own machine.

General Construction

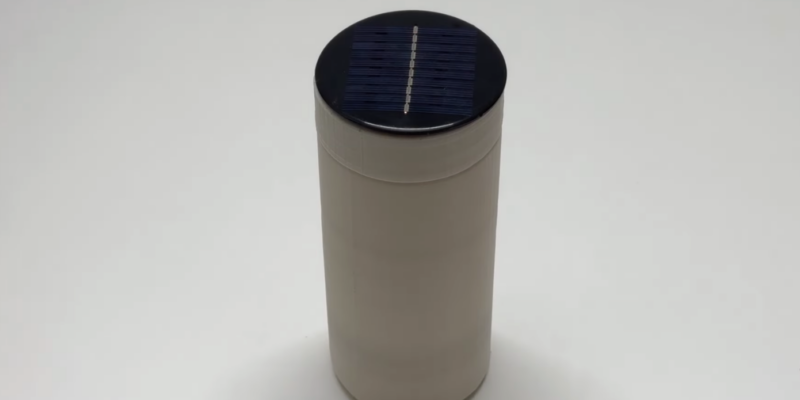

Made from rigid plastic that can be easily worked with hand and power tools, this arcade cabinet is tiny, measuring just 14.5 cm tall × 8.3 cm wide × 8.6 cm depth. Internally there is sufficient space to add your own electronics, including a Pi Zero W, as long as it is mounted to the base of the unit, as this has the greatest surface area.

Power

Powered by three AA (LR6) batteries, we see 4.5 V of voltage, which means we can easily install a LiPo, or other type of rechargeable cells, as long as we use a suitable boost/charging board. Power is then passed directly to the main PCB, which has no power regulation, so careful consideration is needed to ensure the electronics are not damaged.

Electronics

This is a little bit of a Frankenstein’s monster, as the electronics for this cabinet are actually the same as used in the many Chinese clone hand-held consoles that can be picked up for a few dollars online. We can identify this due to six pads on the board, which are normally used with rubber buttons that hold a conductive pad; when a button/pad is pressed, this causes a connection to GND or VCC and triggers a change in state. This then triggers the game to make our character jump, or spaceship fire its weapons. There are six wires that are directly attached to the electronics. These are for power, an interrupting power switch, and the speaker. Connection between the electronics and the screen is via a custom cable, held in place but rather fragile. The screen is a cheap LCD measuring approximately 5 cm × 3.5 cm, but there is scope to add your own miniature screen, and space to add a slightly larger screen, such as those from Adafruit or Pimoroni. Also present on the board are a number of test points, used in the factory to test the board, and we can use them to bridge connections, fix broken wires, and tap into the power supplied from the batteries.

But the most visible part of the electronics is a big grey ribbon cable at the bottom of the PCB. This links to another PCB hidden under the controls. This PCB is tricky to get out as it is screwed in place and you cannot get a conventional screwdriver in there, so we used a ratcheting offset screwdriver and revealed a simple PCB that uses the same conductive pads to detect input. We could easily reuse this board with an arcade-to-USB interface that can provide more functionality and enable us to use the stock controls with a Pi Zero! Upon closer inspection there are also three unpopulated connections for LEDs, so we could use those to add lights to this tiny cabinet.

Conclusion

As a gadget the cabinet is fun, but as a chassis on which we can create our own miniature arcade cabinet, it is sublime. It has the internal volume necessary for a Pi Zero W and a USB breakout board, and we can easily add a new screen to replace the custom display. Being able to reuse the controls via the USB breakout board means the outside appearance of the unit will not change. For £20, this is a bargain and we can have a lot of fun building our own cabinet without the need for a laser cutter or 3D printer! All we need are some screwdrivers and a soldering iron.

Happy hacking!